Joel Burrows on the dangers of Grammarly and better ways to edit.

Grammarly is the editing program that’s everywhere. It’s plastered over Youtube, has 7 million Facebook likes, and even features in my dreams. For those of you that are uninitiated into the Grammarly cult, the app “automatically detects grammar, spelling, punctuation, word choice, and style mistakes in your writing.” After detecting these errors Grammarly will inform you and will “help you write correctly.” Grammarly claims that it helps you write better stories, articles, and essays. Kaz Matsune, a sponsored Grammarly author even said, “That without Grammarly, I don’t think I could have finished my first book.”

After reading, watching and digesting all of these claims, Grammarly can seem rather appealing for a writer. And how can it not? The idea of a spellcheck that also evaluates your writing’s quality sounds like the utopian dream. However, before we all go and sign up for this service, we must ask ourselves this question: does Grammarly live up to its own hype? This program is potentially asking for over 29 American dollars per month. Grammarly’s suggested edits better be accurate and not make one’s writing worse.

Should emerging writers be using this app to shape their own practice? Does this program really improve what you write? And most importantly, if I were to copy a famous story into this software, would the program tear it to shreds?

The first classic I threw into Grammarly was chapter one of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. And oh boy, did Grammarly not like that. The program gave this chapter a woeful performance score of 69/100. The performance score “calculates the accuracy level of your document based on the total word count and the number and types of writing issues detected.” Grammarly informed me that this chapter contained 118 spelling mistakes, 160 cases of incorrect punctuation, and 44 grammatical errors. The app also claimed that this masterpiece has 28 ‘wordy' sentences – which Grammarly notates as “writing issues.”

But are wordy sentences inherently bad, or harder to read? Sometimes a lengthy sentence can improve an article or a story; it can symbolise an unraveling thought, mirror Joyce’s ‘winding galleries and jagged caverns’, be as evocative of Virginia Wolf’s The Waves, and list several examples in order to make a point. Grammarly opposes the lengthy sentence for supposed clarity. It wants sentences to be short and clinical. This, depending on your intention for a creative work, is a destructive edit. It can easily undermine what you want to communicate with your words.

“Yeah right,” you may have just hypothetical scoffed, “Of course Grammarly thought A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man needed edits. It’s an experimental novel from 1916. I bet if you put a more recent book into the app, the results would have been gangbusters.” Well, jokes on you – hypothetical straw man, I Grammarlied a book from last year. I examined the first chapter of Daisy Johnson’s novel Everything Under. It received a C+ with a score of 79/100. Apparently, this Man Booker nominated story has 7 spelling errors, 11 punctuation mistakes, and 88 “additional writing issues.” Either Grammarly is wrong about most of these errors, or Daisy Johnson should have fired her personal editors, the publishing houses’ editors and ultimately Vintage Books itself.

I even decided to pass Grammarly’s own FAQ page through the editing program. It came back with a performance rating of 96%. That’s right, their own FAQ page contains five “writing issues.” According to Grammarly, this information remarkably possesses one case of “Politically Incorrect or Offensive Language.”

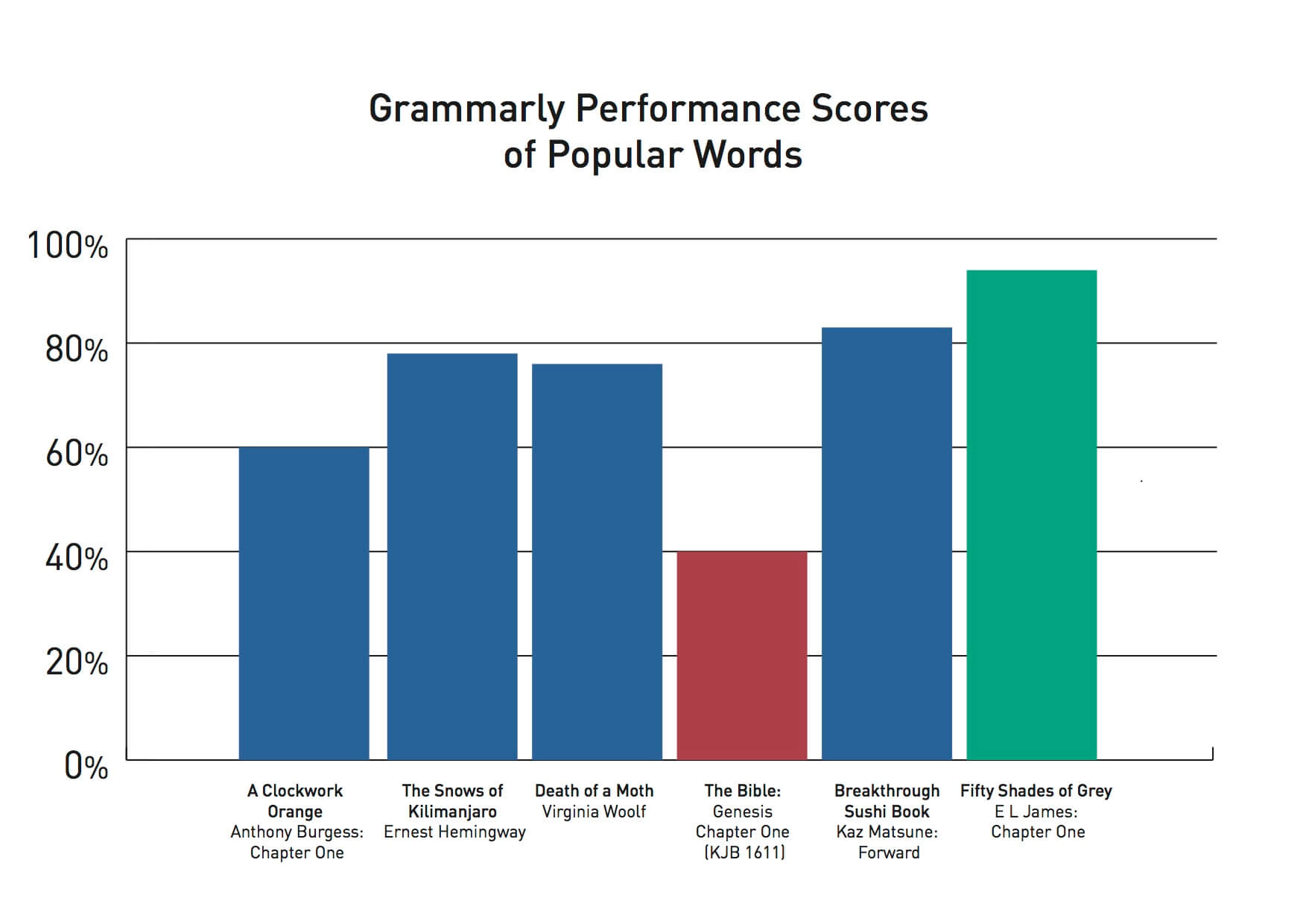

Here is what Grammarly thinks about some other books and articles:

So, what does this graph teach us? Well, it demonstrates that there is no direct correlation between quality writing and Grammarly’s performance scores. Grammarly cannot understand your intent – not every mistake it will find will be a mistake. Therefore, we as writers must find effective ways of self-editing.

Unfortunately, editing one’s own work can be a daunting task. It can be rather frightening to make changes without a robot grammar butler on your side. However, knowing how to self-edit is far more valuable and enriching than just pasting your work into a website. Here are five quick and easy ways of improving your own work:

1) Make structural edits before grammatical edits

It is far more difficult to work out pacing, voice, and tone than it is to work out where a comma is supposed to be placed. Don’t be fooled into thinking that spellchecking is the same as vigorously integrating your own work. Ask yourself if the piece is engaging. Ask yourself if it flows. Ask yourself if what you want to say is being reflected in what you wrote. Once you are happy with the structure of your piece, then you can move onto amending the grammar.

2) Style manuals and Google are your friends

If you are serious about getting into the editing game, get yourself a style manual. I personally use the Australian Government's Style Manual. It covers everything from proofreading marks to textual contrast, to the basics of spelling and grammar. Who knew ’n-dashes’ were a thing. And if buying a super nerdy Style Manual isn’t your thing, then goodness gracious: you are on the internet. It literally has one-hundred articles written about every grammatical rule. You could even create a little checklist of the issues that you often struggle with.

3) Write and edit on different days

You would be amazed at how many structural and grammatical errors are illuminated by just leaving your work for a day. Your story or article can suddenly go from near perfect to needing a whole bunch of rewrites. Creating your work this way can also solve the problem of perpetually editing that first paragraph. (Don’t lie, we all struggle with this.)

4) Read your work out loud

Look, you may feel ridiculous. You may bamboozle your neighbours and dog. However, if want your writing to sound more human and colloquial, then this editing technique is for you.

5) If it’s important, print it

Many articles and research essays have noted that humans interact with text differently depending on whether it has been printed or not. Professor Barron in Why Digital Reading is No Substitute for Print states, “Print was… easier on the eyes and less likely to encourage multitasking.” She also notes that when she studied student’s reading patterns and preferences that, “Print stood out as the medium for doing serious work.” Therefore, the next time you're working on your novel or your next big feature, consider dusting off the old printer or running down to Officeworks.

6) And if you’re going to use Grammarly anyway…

I’d recommend using only the free version. Know that a tone of suggested edits are superfluous or can actually damage your writing. Understand that Grammarly isn’t a substitution for a structural edit or knowing the rules of grammar. And most importantly, ignore that score sheet that it gives you. In no way does that score reflect the quality or importance of your writing.

So, that’s why Grammarly can be a bit rubbish. If you are still dubious of my conclusions, or doubtful of my tips, please remember this: I am factually a master of English. This very article received a Grammarly score of 82/100. The first chapter of Ulysses only received a 71/100. I am therefore a better writer than James Joyce and everything I ever write should be taken as gospel.

I look forward to this article becoming a celebrated Penguin Classic.

Joel Burrows

Joel Burrows is a journalist and playwright. His writing has been featured on The Guardian, Going Down Swinging, and this very website. In 2019, he is writing a new play with support from the Merrigong Theatre Company.