An ideas piece by Lauren Fuge on how being immersed in a new language re-ignited an old flame.

I rocked up in Munich with a year and a half of language learning under my belt, knowing I wasn’t going to cut it. With a reading level of seven-year-old, I felt my age acutely—in bakeries I stumbled over asking for Brötchen (bread rolls); I frantically typed into Google translate at restaurants and ticket machines; and I spent anxious evenings in a many-cornered classroom at the local Volkshochschule (adult learning centre).

Around my German girlfriend’s family I became a quieter, simpler version of myself, barely ever asking for translations to avoid the possibility of embarrassing myself. I diluted my opinions because I lacked the vocabulary or tense structure; if I tried to express anything too complicated it sounded like my words had been through a grammatical blender.

Almost every single person I met was patient with me, but in groups their words would speed up, thicken into dialect and bleed into laughter. I’d listen until my head swelled with the weight of their words, feeling like a four-year-old at the adult’s table. The slow and frustrating immersion in German made me feel like I was living through a second childhood where I had to relearn how to interact with the world.

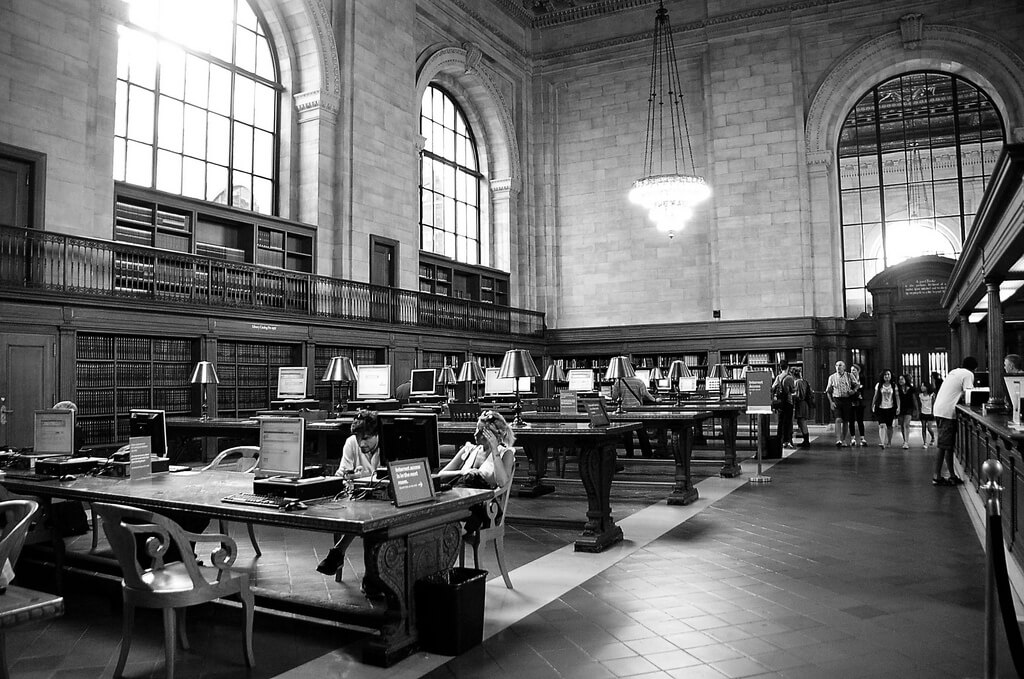

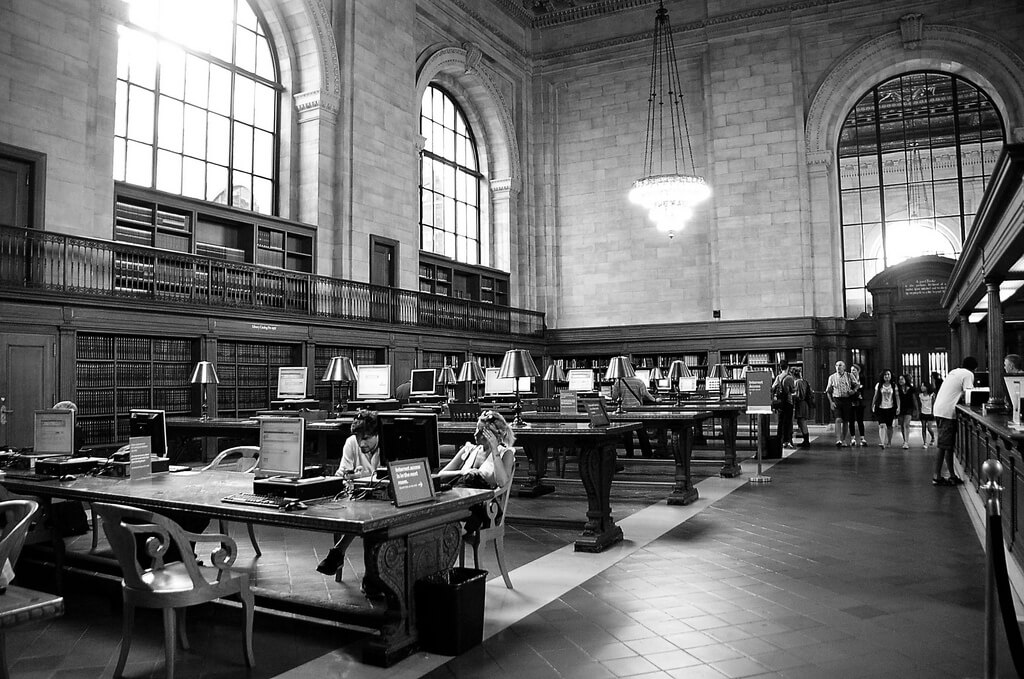

But Munich itself offered me a familiar way to connect with the language. The city is more than just rowdy beer halls and spectacular churches—it’s a city rich with literary history. It’s one of the biggest publishing hubs in the world and is known nation-wide for its lively literary scene, literary luminaries, and vast array of bookshops and libraries. So one frosty Saturday morning, I worked up the courage to visit my local library and ask, in shaky and well-rehearsed German, for a library card.

Fifteen minutes later, I found myself on the top floor where the windows overlooked the town square, fingers trailing along the spines of books for six to nine-year-olds. Kids in bright dinosaur-patterned jackets raced around me, and in the corner, grandparents sat on comically small chairs to read picture books to dribbling toddlers. I selected a slim book with big block letters on the spine, carefully flicked through the first pages, and sat down to read.

Within a few weeks the small bookshelf in my boxy apartment was packed with kids’ books. I read them voraciously after work, zipping through without bothering too much about comprehension—just like how I read as a kid in English, valuing speed and excitement over understanding. I read books that were too easy, too advanced, books that I’d never read before and books that I’d loved as a kid in English. The benefits were two fold—my German was steadily improving, and I felt secretly lucky to have an excuse to experience the wonder of kids’ books again. Almost every Saturday I’d be back to return last week’s haul and then clatter up the stairs for more.

When I visited my girlfriend, she swiftly introduced me to Erich Kästner. In her household and in much of Germany, he’s the most beloved children’s writer in existence. Together we watched movies made of his classics—Emil und die Detektive (Emil and the Detectives), Das fliegende Klassenzimmer (The Flying Classroom), Pünktchen und Anton—and then I borrowed each of the original books to relive the magic. I fell in love with Kästner like I was eight years old again. In Pünktchen und Anton there’s a scene where the main character busks in an underground U-bahn station in Munich, her whirlwind energy enchanting in a crowd of clapping strangers, and one weekend my girlfriend and I descended down into a subterranean maze and found the spot where the girl had busked. We lingered for long minutes, replaying the song in our head, childishly delighted to be connected to this place through story.

But as much as I’d come to love German kids’ books, reading in English was a relief. My local library had three squashed shelves of English books in the basement, and I often took home old favourites. I read every Cornelia Funke book the library owned in English and realised—feeling pretty stupid—that every single one is a translation of the original German. So I read the German versions too.

One bright Sunday I biked to the lake and sprawled on the grass with an English copy of The Book Thief. My version back in Australia is well-thumbed and decorated with dozens of post-it-notes, but as I cracked open the library copy and traced the familiar words, new connections formed like constellations. The book, I realised, is set just north of Munich, in a fictional town in a very real place along a very real river—a river that links up to the lake I was sitting in front of. If I’d jumped back on my bike, I could’ve arrived at the supposed location of the town in twenty minutes. It was an odd and disconcerting discovery; where the town was hadn’t seemed relevant before, but right now it was the most relevant part of the book. I felt a rush of pure affection for this city, cementing me to this grass, this water, this land.

The weird parallel didn’t escape my notice—I was rereading the books that shaped my actual childhood in the place where I was going through a second childhood, where I was being shaped yet again by stories that allowed me to connect with the place and the people around me. Germany was a new world for me, spinning with a language I still haven’t got a grip on, but the frustration was worth it for the opportunity to relive the wonder of kids’ lit all over again.

Banner image: Flickr, Eugen Anghel

Feature image: Flickr, Britt Reints

Ideas

Ideas