...and how every story is basically Harry Potter.

I’ve been telling myself (by which I mean people at parties) that I’m a writer for a good fifteen years now, which would be fine, if I’d learned how to write a decent story fifteen years ago

It took me an embarrassingly long time to work out that a story needs to, you know, tell a story. That is, unless you’re grappling with a nebulous post-modern alt-lit as you would a bar of soap in the bath. If you're not, then your story needs a character and that character needs stuff to happen to them.

It sounds basic, but I’m amazed by how many people (who yes, tell me they’re writers at parties) don’t do it.

Here's the easiest way in the world to structure a story.

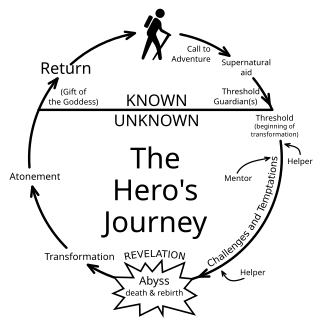

Way back in 1949, a scholar named Joseph Campbell came up with the idea of the monomyth, in which he pointed out that pretty much every story ever told by humanity, across all its myriad countries and cultures, are more-or-less the same story, just changed slightly to fit into different ideologies and cultures. He breaks this whole thing down in his book The Hero's Journey, but in a nutshell it works something like this: a regular person has something unusual happen to them, goes on an adventure, goes through something unpleasant, and returns to where they started the story having learned something important about themselves/saved the world.

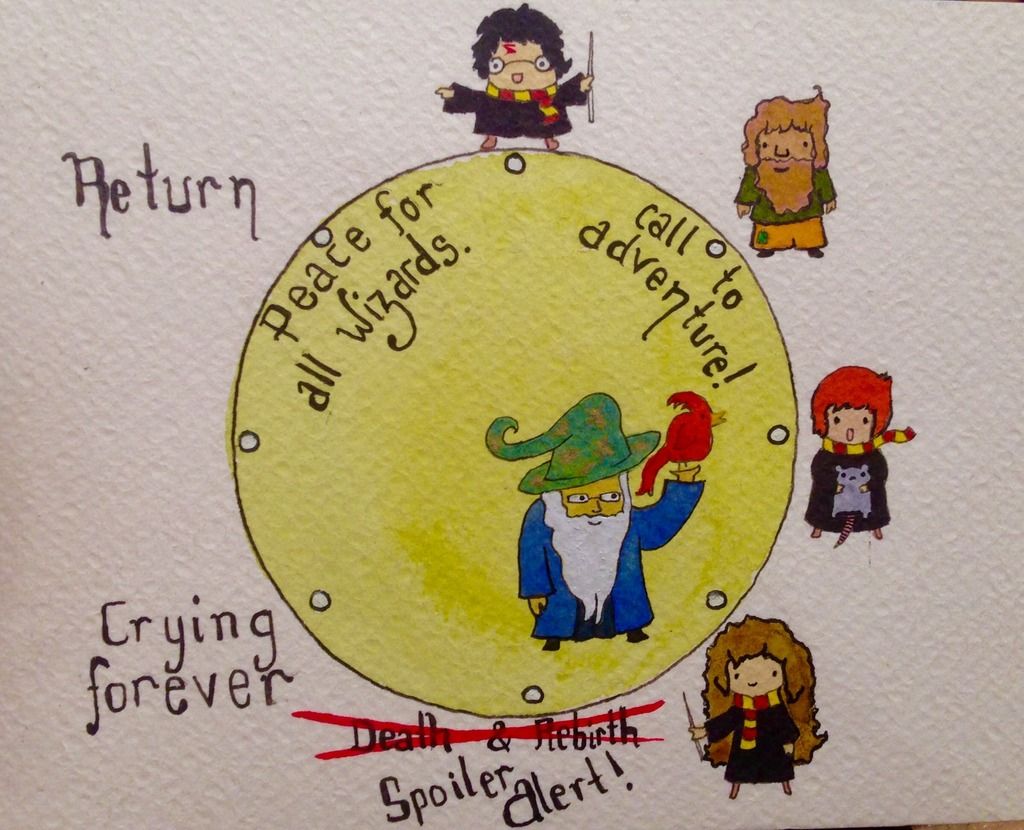

It looks a little something like this:

You could read the book, or you could do what’s always worked for me, and cheat! Do this thing I stole off Community Show-Runner Dan Harmon and put it over your desk, and refer to it next time you write a story.

Draw a circle. Divide it in half, and then in half again. Number it one to eight from the top of the circle all the way around in equidistant sections. Assign one of eight key story beats to each number. These are:

1. A character is in a zone of comfort,

2. But they want something.

3. They enter an unfamiliar situation,

4. Adapt to it,

5. Get what they wanted,

6. Pay a heavy price for it,

7. Then return to their familiar situation,

8. Having changed.

This is your story circle and it's going to hold your whole plot and character arc within it.

Let's look at this structure as it is applied to say...HARRY POTTER.

1. You (a character is in a zone of comfort)

Establish a protagonist: Harry lives under the stairs with his awful family. He is not a wizard.

2. Need (but they want something)

Something is missing from your protagonist's situation. In this case, it’s because Harry isn’t a wizard, even though he can talk to snakes.

3. Go (they enter an unfamiliar situation)

Harry meets Hagrid and accepts the offer to go to magic school. Hijinks ensue.

4. Search (adapt to it)

This is where your protagonist faces a bunch of trials and adapts to them, experiments, is broken down and rebuilt. Harry makes friends, is bullied by Draco, who is a jerk. He is also bullied by Snape. Ugh. That Snape. Such a bad time.

5. Find (find what they wanted)

In the Monomyth, this section is called 'Meeting With The Goddess', in which the need from step 2 is fulfilled. In this case, Dumbledore is the Goddess who teaches him both the value of magic and selfless sacrifice.

6. Take (pay the price)

This is the hardest part of the journey – in Harry Potter, this is the rise of the Death Eaters, Voldemort's rampage, the loss of friends and loved ones.

7. Return (and go back to where they started)

This is where you bring the story home, often literally. The wild adventures are over. Harry has defeated Voldemort and he can stop fighting. Bringing it home.

8. Change (now capable of change)

The protagonist is now the agent of change in the story, and brings whatever he discovered on their adventure back to the normal world. In Harry's case, it's peace in the wizarding world. Harry can settle down and have kids and a normal life, but he will always remember what he has learned from Snape and Dumbledore, and he will always be the one who saved the world. Draco is still a jerk.

And there! Just another iteration of a story told time and again. Take this structure and apply it to the next thing you read, whether it's the highest fantasy or Canadianist realism—here’s an outline of every Alice Munro story:

1. A woman is unmarried.

2. She sometimes thinks about the man she might have married.

3. She has tea with the man she might have married.

4. He says something that makes her remember a thing he said a long time ago.

5. She thinks about the past for five pages.

6. She decides she is ambivalent that she didn’t marry the man. The man leaves.

7. She returns to her home.

8. She decides that she was right not to marry that man. She drinks some tea.

So there you have it, the basic shape of every possible story. You’ll find that not every beat seems obvious in all stories, but it will be there in some form. That’s the difference between story and style which is a whole other thing, which we'll get to another day.

Go and try this on your next story, or go back and build the beats into an old story of yours that didn't work.

It’ll help, I promise.