Literary Cities

Literary Cities

Literary Natal

Brendan Zietsch sends a Literary Postcard from Brazil's cultural cradle. Obscure, impoverished, difficult to get to for almost everyone in ...

Read MoreClaire Rosslyn Wilson, on the beauty in the burning fires of Valencia, Spain

The smoke is there the next day, caught up in the threads of clothes. And not just the ones I’d been standing in as I watched the fires burn – everything in my cupboard has the whiff of burnt wood. I open the windows and the smell of smoke sits over the city. The fires are out, but their residue will linger for another few days. Andy Warhol catalogued his life into three-month segments of perfume, his scent museum that he’d sometimes wander into, un-stopper a smell and remember. In Valencia I bottled smoke.

Smells catch me by the nose

disappear at will,

perfumes I haven’t annotated.

Valencia is a city that burns in March, every March since at least the 18th century. Most cities and towns in Spain have local festivals based around patron saints or the change of seasons and Valencia is no exception. From 14 to 19 March Valencia celebrates St. Joseph's Day, the patron saint of workers, and the onset of spring in a festival called Fallas.

So what’s so special about Fallas? For a week this Mediterranean city is one big party culminating with mass burning of wooden and paper-maché effigies across hundreds of squares and parks. Some as tall as buildings, the monuments provide a commentary on current social issues, often mocking current politicians or celebrities. Those involved in building the monuments take all year to prepare them, often passing on the skills through family generations. In the five days of celebration every street in the city comes alive with movement and sound, a street party that takes over the whole city of 1.5 million people (and more with visitors during Fallas). There are parades, beauty pageants, bands, early wake-up calls, street paella cooking competitions, fireworks, firecrackers, street lighting competitions, an enormous Virgin Mary made of flowers, parades in traditional dress, outdoor feasts and night parties.

The square awash in flowers,

their scent

gives me headaches.

It becomes a test in endurance. Early starts, endless evens during the day and late night gatherings mean that many locals looking for calm escape to the country in March. And although Fallas celebrates the onset of spring, it’s still elusive. The cold hasn’t yet disappeared entirely and when the sun retires it feels like winter’s fingers still grip exposed skin.

This is Fallas.

Rice smoked on street-side fires,

ten cooks all decide

it’s uneatable.

The festivities begin long before the official holiday. Throughout March at 2pm every day there is the Mascletà. Held in the main square in front of the town hall it’s a ten-minute gunpowder show. Tied low to the ground firecrackers are set off in an arranged rhythm that the locals will tell you is music. As the space between the small explosions shortens, smoke rises and the intensity increases, until the ground beneath your feet is shaking. The composition descends into noise as the packed square feels the Mascletà overwhelm them, noise rising to engulf heads. It stops abruptly, leaving smoke and ringing eardrums loitering with the crowd.

These explosions are also held on a more moderate scale throughout Fallas in the local neighbourhoods. Held in much smaller squares the sound might be less intimidating, but there’s a chance to get closer to the moderately controlled bangs.

Smoked clothes,

not the season

to hang out your washing.

Sound takes over the city throughout Fallas. If it’s not the before-lunch explosion-compositions, it’s the 8am wake-up call of musicians leading their brass-band processions through all their neighbourhood streets. And did I mention the small firecrackers thrown from behind the bands?

Footfalls gone

in a puff of smoke,

we’re all magicians here.

The festival is bookended by the mounting of the monuments on street corners and squares, and the burning of them only days later. But what holds Fallas together is the community who builds these condemned effigies. The monuments represent a year of work, of meetings, fundraising and events. As they stand on the street they are surrounded by a neighbourhood that has built not only the structure, but the community around it. As commented in the UNESCO recognition of the festival as intangible cultural heritage, Fallas symbolises ‘the coming of spring, purification and a rejuvenation of community social activity.’ This social cohesion of the community is at the heart of the festival and is something that is still very much alive today.

And then comes the night of the burning, the Cremà. For a year artists and artisans had been designing monuments and then on 19 March they watch them burn to the ground in a matter of hours. The children’s monuments are burnt first at 9pm and then the larger ones are lit at midnight.

The fires starts from a hole made with an axe at the base of the monument that’s stuffed with kindling. The flames heat from the feet up, smoking as the flames take hold from the inside, soon reaching through to dance around the shapes that look like people. It eats them, limb by limb, lighting up the silhouettes as they turn the layers of skin black. Outlined against orange the figures could be burning people, except that they’re still and silent. There’s just the sound of the flames eating themselves out of fuel.

Smoked out smiles play with flames

haze slides on all our skins,

we watch it burn.

Blackened figures hold out wavering arms before they collapse into the heat. At this point it becomes hard to watch the flames directly, the heat driving the crowds back a few steps and then a few more, pushing people to the edges of a square or onto surrounding roads. The flames push out their heat to warm watching faces. The shapes in the monument lose their cohesion and collapse in on themselves with rising sparks, revealing the main structure that held it all together. They crumble in stages and soon compress to a pile of coals that grow cold as the crowd moves in again. It doesn’t take long to burn from form to ash.

Charcoal holding together,

an outline in orange

undoing in the heat.

Our faces cool, excessive heat turns to an absence as we start to feel again. Our clothes smell of smoke, an outside world sauntering into our houses to pass from thread to thread, the last reminder to linger for a while.

But the smoke soon gets sucked out open windows to lose its focus with the residue of other activities overlapping one another in scenes of daily life. Until the next year.

Claire Rosslyn Wilson is a poet and nonfiction writer. She is a regular writer for Art Radar and Culture360 and has co-written a book on Freelancing in the Creative Industries (Oxford University Press). She’s had her poems published in various Australian journals and she writes short poems about the everyday objects around us at http://clairerosslynwilson.com/ You can also follow her thoughts @clairerosslyn

Literary Cities

Literary Cities

Brendan Zietsch sends a Literary Postcard from Brazil's cultural cradle. Obscure, impoverished, difficult to get to for almost everyone in ...

Read More Literary Cities

Literary Cities

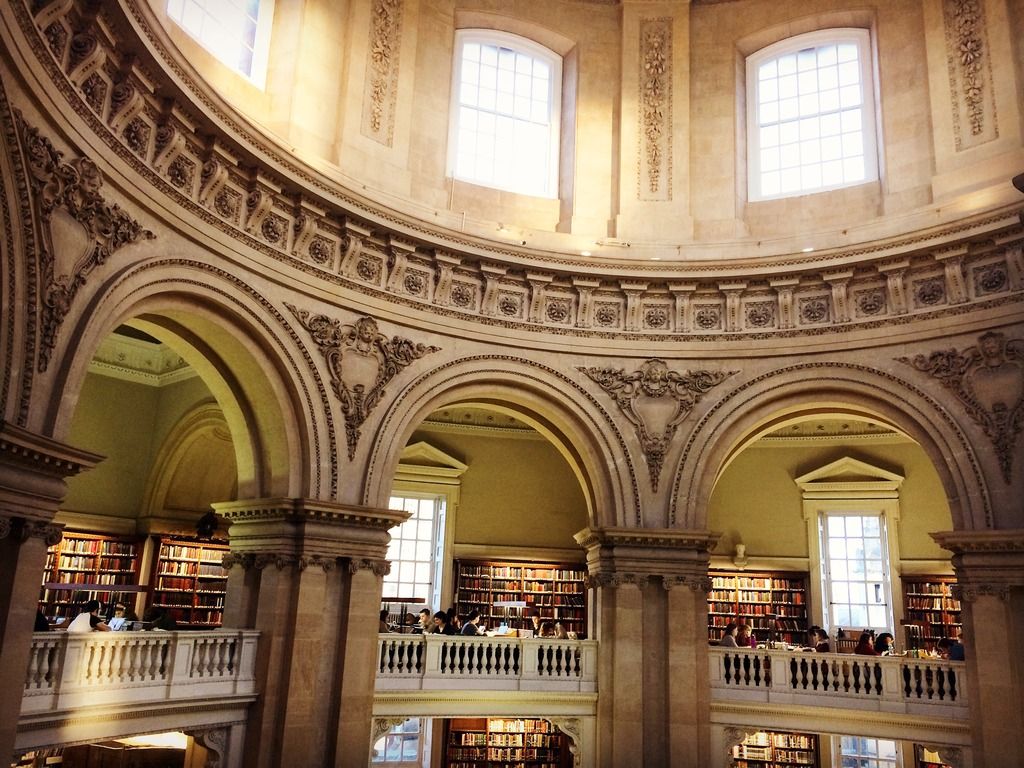

This is a literary postcard from Oxford, by Rebecca Slater. I came to Oxford to write. I tell myself this most mornings, particularly these dark ...

Read More Literary Cities

Literary Cities

This is a Literary Cities postcard from Karratha, by Megan Hippler. When my employer in San Francisco sent me to Karratha for a month, the ...

Read More