This is a Literary Cities piece on Paris, by Donna Lu.

My mum hates Paris. The first time we visited as a family, all my worldly possessions were stolen at the Gare du Nord. It would have been a disappointing day for the thief, who, upon discovering he had nicked an eight-year-old’s backpack full of colouring pencils and Deltora Quest books, must have kicked himself for not picking up the neighbouring bag, which contained my parents’ money and camera.

The last time my mum visited, she was mugged by two gypsy women, who prised open her handbag before she yanked it back and escaped unrobbed. I teased her for booking accommodation in the seventh arrondisement, in a touristy area that was too close to the Eiffel Tour. There were other complaints, too – that people were unhelpful, didn’t speak English (quelle surprise), and that food was too expensive. Apparently, on the holiday when I was eight, they had been too poor to afford eating at restaurants. I remember learning merci from the bins at McDonald’s (why they decided a family trip to Paris was a good financial decision is beyond me).

It doesn’t help that my mother is statistically more likely to have a bad time in Paris. Since China’s economic boom, hatted tourists have descended upon the ville d’amour in droves, marking us yellow skinners as prime targets for petty crime. “Reported violent robberies targeting the Chinese community, who are seen as lucrative prey as they are thought to habitually carry large sums of cash, have tripled in the past year, from 35 to 105,” reported France 24 a few weeks before I write this.

So it was much to my mother’s bemusement that I decided to spend time in Paris in the summer of 2015, much of it alone. The last time I’d visited was five years previously, in the same July heat that clings to your skin and lingers thickly in the night air.

I booked the trip on an idealistic whim, feeling encouraged by my now-passable level of French. Paris seemed full of promise and possibility. If you let it, the city’s history and culture and architecture swallow you up, and soon enough you envision yourself (or, at least, who your future self could be) as one of those chic Parisiennes who plays pétanque by the Seine, smokes wantonly and idles for hours over a cooling meal. Perhaps if you stay long enough, something in the water or air will smooth your body to the city default: a lithe being, whose never-ending legs pedal bikes down the rue de Rivoli in dresses, and whose sweat glands have been dialed down to prevent everything more than a radiant glow.

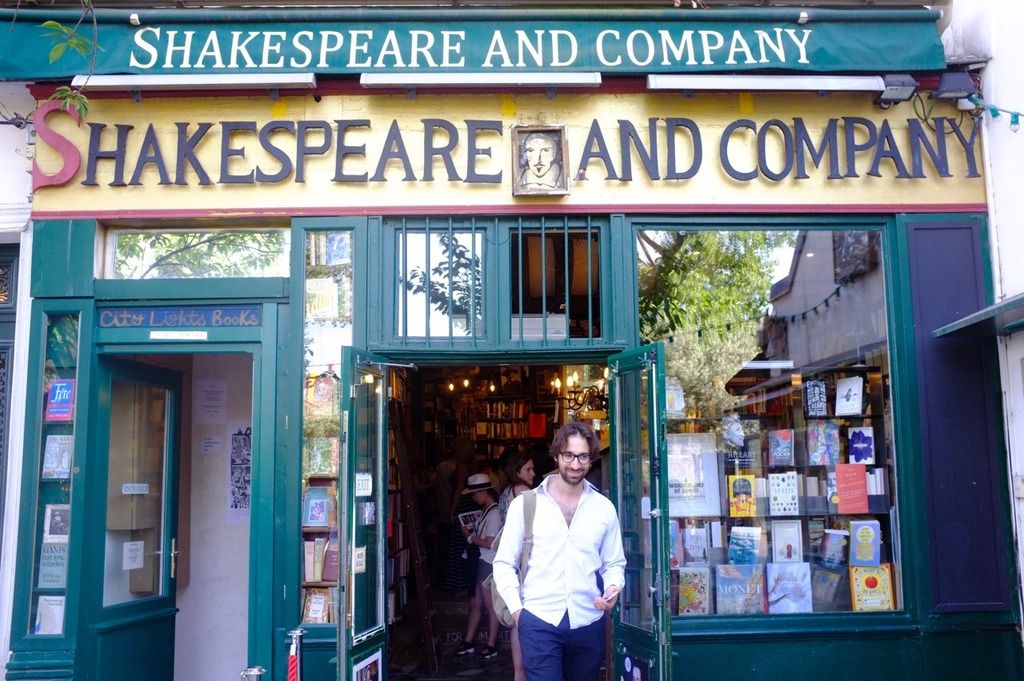

In preparing for my first trip alone to Paris, I daydreamed of being a Tumbleweed at Shakespeare and Co., the city’s largest English-language bookshop, where I could live in a nook in the Russian literature section and make friends with a literary expat set. In Saint-Germain-des-Prés, I would make like the Lost Generation, and scribble things into a Moleskin at Les Deux Magots or Café de Flore like Hemingway or Simone de Beauvoir once did.

When I got to Saint-Michel, the area Shakespeare and Co. is located in, the alleys were overcrowded, with crêperies every which way, Americans wearing fanny packs, and garish souvenir shops hawking fridge magnets and sunglasses. At Café de Flore, well-to-do foreign families sipped on seven-euro Cokes. I gave it all a miss.

And yet how diligently I clung to cliché. A canicule, a heat wave, descended upon France, and as the elderly expired in their high-ceilinged Haussmann apartments, in 38-degree heat I pottered around the Père-Lachaise Cemetery. Resting for shade in tree-lined lanes, I wandered to the graves of Oscar Wilde, Proust, and Balzac. In appreciation, the literary gods repaid me with sunburn.

The rosiness of the glasses always fades. Walk for long enough in Paris and you’re bound to kick up grit: a woman getting followed and harassed by drunken louts along the Canal Saint Martin; a family asleep on a mattress in Saint-German-desPrés, the young son’s lips cracked in the noonday sun; my friend Laura getting stranded in the middle of nowhere when her train from Charles de Gaulle airport was stopped by protesters on the tracks; pickpockets at the Gare du Nord; women lurking in alleys in the seventh.

Yet despite all this, despite the petty crime and lines in summer and too-often strikes and rudeness of boulangers (or, at least, of whoever is serving), the city’s appeal endures. Paris is still one of the most visited places in the world. Henry Miller’s description in Tropic of Cancer seems to sum up the city’s perverse attraction:

Such a huge Paris! It would take a lifetime to explore it again. This Paris, to which I alone had the key, hardly lends itself to a tour; it is a Paris that has to be lived, that has to be experienced each day in a thousand different forms of torture, a Paris that grows inside you like a cancer, and grows and grows and grows until you are eaten away by it.

Cutting through the summer idyll were the soldiers who dotted street corners, their machine guns a reminder of a city on edge. This was after Charlie Hebdo and before the horrors of the November 13 attacks. At the Place de la République, where millions had gathered in January, chanting, ‘Charlie! Liberté!’ there were still flowers, messages and Je suis Charlie signs.

It was a tragedy set against a background of tumult. The city’s sights are all the more impressive for their history: the Champs-Élysées, empty but for the Nazi tanks that rolled in; the front of the Notre-Dame boarded up with sandbags to protect it against bombing; walls of empty frames in the Louvre, the artworks evacuated to the French countryside during the Second World War; even the Eiffel Tower, arguably the symbol of the city, whose construction was opposed by the likes of Alexandre Dumas and Guy de Maupassant, who decried it as “useless and monstrous”.

After the Bataclan attacks, I wrote to a friend who lives in Le Marais, to check he and his partner were safe. J'espère que Paris redeviendra vite lumineuse et belle, he replied. I hope that Paris will soon be bright and beautiful again. And quickly it was: je suis en terrasse (I am on the terrace) became the catch-cry in the wake of the attacks; young people flocked back to bars and restaurants, back to small street-facing café tables, to show they weren’t afraid.

Paris recovered from the tragedies of Charlie and Bataclan, grieving but with its soul intact, as it has done after wars and revolution. These incidents have sorely tested, but did not, and cannot, break the city’s indomitable spirit. Paris will go on being romantic, gritty and altogether enthralling.

This is a Literary Cities story, part of a series where writers reflect on the places and experiences that have inspired them. To read more like this, click here.

Make sure don't miss out on any of our content by signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Donna Lu

Donna Lu is a Brisbane-based writer who has previously contributed to The Atlantic, The Guardian, and VICE. She tweets @donnadlu.