This is a Literary Cities piece by Elizabeth Flux about Hong Kong.

Every night, after tucking me in, and before saying goodnight, my mother would do two things: read me a story and give me a spelling test. Living in Adelaide in the early ’90s meant that the selection of Chinese-language children’s books was pretty much limited to the ones we’d brought over ourselves from Hong Kong when we migrated. She’d pull one of the beautifully illustrated hard-cover volumes off the shelf, open it from the back, and read down the column of spiky characters, stopping at the end of each sentence for me to repeat back the monosyllabic sounds to her.

From time to time she would stop and correct me until my tone was perfect—important, as, with Cantonese being a six tone language, almost every word is a double entendre waiting to happen; the small difference between “bitter” and “trousers”, for example, being a lapse of concentration away from making you a dinner party laughing stock. See also: “boarding a plane” and “masturbating”.

We’d finish the story and then she’d pull out the Look-Cover-Write-Check folder, running me through the words until it was a given that I’d get 20 out of 20 for that week’s test at school. This was our routine for years. My spelling and English skills improved as I got older and moved through the grades. My Cantonese, however, reached its peak early on and stayed there.

In one visit back home, a friend of my cousin’s shared his theory that people in Hong Kong were shorter than they might otherwise be “because there is less space, there is less room to grow”. He then pointed to my (very tall) cousin and laughed, saying “but there are exceptions to every rule”. In a weird kind of way, this is how I feel about Cantonese, which is neither my first nor second language. I learned both at the same time, but while one was given room to flourish and expand in the space and environment surrounding me, the other, limited to the hard hours my mother put in and occasional phone-calls to relatives, remained ever smaller, always slightly withered.

Earlier this year, I went back to Hong Kong on my own for the first time. I was nervous. My primary fear was that my knowledge of the language would have atrophied to the point of being incomprehensible; having long moved interstate and out of home, my opportunities to speak Cantonese in Australia had shrunk even further. All I had were sporadic conversations with friends in the same situation, a handful of ticket stubs to the few Johnnie To movies released here, and again, the occasional phone-call to family.

Beyond this, however, I was afraid that I would be too timid to even try. Hong Kong is a truly international city, and, like so many other places around the world, English is treated as an almost universal language. There will always be two signs, two sets of instructions, two menus. If you don’t want to, you don’t have to try.

My father, when we lived there, had valiantly tried to delve into the language, but fell victim to The Curse of the Tones. Hearing the almost inaudible distinctions between words is something you probably need to have drilled into you from childhood. He walked into a shop and asked for bread—mian bao—and, after an awkward pause, walked away with (somewhat ironically) a specific Cantonese-language newspaper—Ming Pao.

On landing I steeled myself and bought a train ticket into Central speaking only Cantonese. The man behind the counter gave me some instructions on which lines to catch. I handed over the correct money. No-one accidentally said “masturbating”. It went fine. So did my next conversation. And the one after that.

In the three weeks I was over there, my confidence grew, as did my vocabulary—with a small dip when I learned that for years when I thought I’d been referring to “fly” I’d actually been saying “eagle”, making my complaints about being swarmed by them somewhat confusing.

Underlying it all, however, one thing—other than repeatedly being swarmed by eagles, of course—started to bother me more than it had previously. I’m fortunate to be able to speak my language, but as a writer, it creates a strange divide in myself when I acknowledge that I can neither read nor write it.

I can order mian bao, yes, but I can’t read a Ming Pao. I can have day-to-day conversations, but I can’t engage fully on a local level. There are stories that I will never know. Like all languages, there are words that don’t translate, jokes that only make sense when told in their home tongue; in context. For me, Cantonese is exclusively in-person—I can only record my thoughts partially removed, one step away, through English—through a filter.

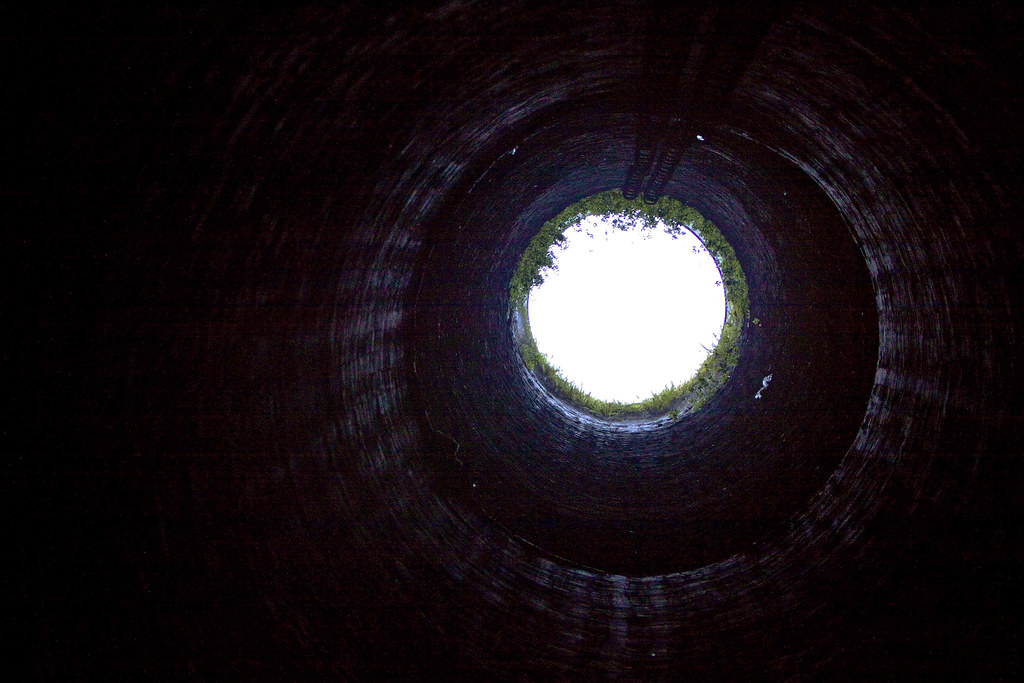

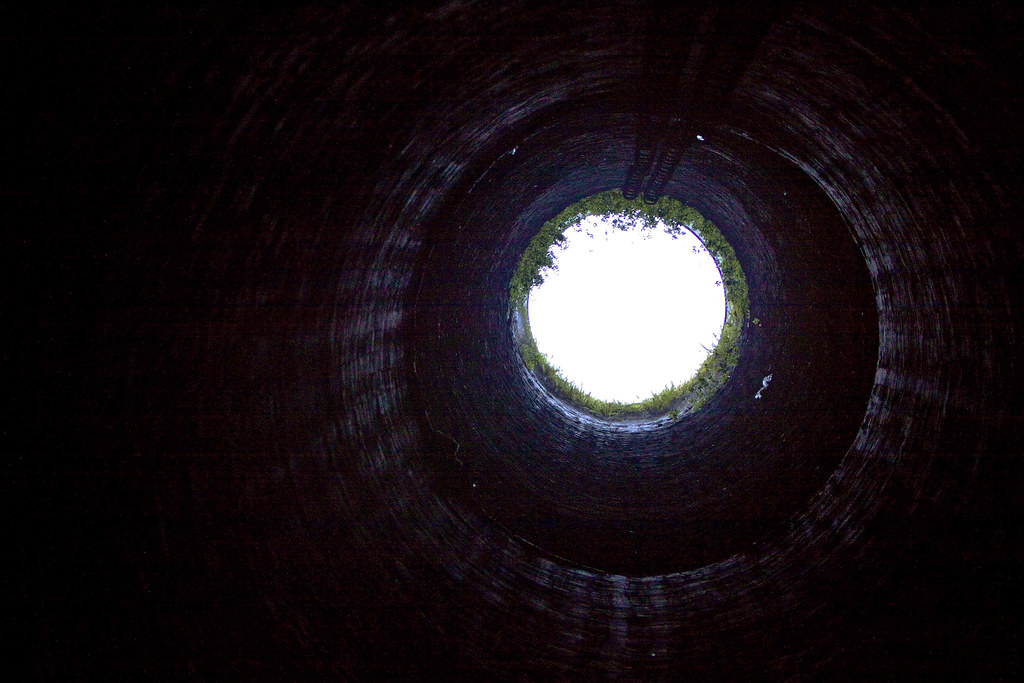

After we finished with the fairytales, my mother moved on to teaching me idioms. My favourite (after the one about blind men touching an elephant and describing the experience to each other) is zheng dai ji wa – frog at the bottom of a well. It’s the story of a little frog who has spent his entire life thinking that the world is nothing but the circle of sky he is able to see. When an eagle (not a fly) passes overhead and describes the ocean and mountains that surround them, the frog refuses to believe a word of it.

We all start out as the frog and expand our worlds in different ways. For me, Cantonese has been a big part of that. It’s a strange space to occupy when two languages inform the way you think; it’s made me good at differentiating the literal from the metaphorical, and I’m quietly confident that the heavy focus on tone is why I am inhumanly attuned to puns. Its most (currently) relevant lesson, however, is knowing that when you’ve said enough, it’s time to stop talking. Mou wak se tim juk – don’t draw legs on a snake.

This is a Literary Cities story, part of a series where writers reflect on the places and experiences that have inspired them. To read more like this, click here.

Make sure don't miss out on any of our content by signing up to our weekly newsletter.

Elizabeth Flux

Elizabeth Flux is a freelance writer and the former editor of Writers Bloc. Her nonfiction work has been widely published and includes essays on film, pop culture, feminism and identity as well as interviews and feature articles. Her fiction work has been included in numerous anthologies including Best Australian Stories 2017 and The Legend of Monga Khan, and she was the winner of the inaugural Feminartsy Fiction Prize. She is an editor for Reading Victoria and previously edited Voiceworks and On Dit. Twitter @ElizabethFlux